Author: Sofia Boarino, architect, researcher, and sound artist.

The architectural design of learning environments holds the power to shape our minds and bodies. Elements such as light and sound—seemingly intangible—profoundly influence perception, behaviour, emotional regulation and neurophysiological function. In educational contexts, where development and cognitive growth are paramount, it is essential to design not only for visibility or silence, but also for circadian alignment, emotional engagement, multisensory coherence and connectedness.

Light is more than a tool for visibility: it structures time, perception, memory and emotion. It entrains circadian rhythms, affects hormone production, modulates our biological clock, and guides psychological and psychological rhythms across the day. Almost all bodily functions change as the day progresses: body temperature, alertness, and mood fluctuate, while the melatonin rises at night and falls during daylight. This rhythm is regulated by the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus, which receives direct input from melanopsin-sensitive retinal cells particularly responsive to blue light (460–480 nm) [Georgieva et al., 2018; Münch et al., 2012]. Light is in fact used as therapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder, depression, ADHD, Parkinson’s and dementia by aligning circadian rhythms and influencing serotonin regulation [www.chronobiology.ch]. This has led to the development of Human-Centric Lighting, systems that mimic daylight’s spectral shifts throughout the day. Products like Philips Hue or advanced integrated LED systems offer chronobiological compensation, translating sunlight’s variations to support attention and rest cycles. The benefits are highly significant across fields. Applying these technologies to schools for instance, is particularly critical, as children’s circadian systems are still developing and are highly susceptible to light-induced phase shifts [Rivkees, 2004]. This would mean starting the day with 12,000 kelvin light to stimulate alertness, shifting to 6,000 kelvin during periods of concentration, and then moving to 3,200 kelvin to promote calm. This approach reflects how blue-enriched light in the morning enhances wakefulness, while warmer, amber tones in the afternoon help signal the body to wind down [Yousif et al., 2023; Llinarès et al., 2021; Georgieva et al., 2018].

However, this way of designing, especially in workplaces and learning environments, often remains too focused on efficiency and performance. Where environmental conditions permit, school schedules should enable children to wake naturally with daylight and begin their day when it is already bright, rather than relying on intense blue-enriched lighting to artificially induce alertness in the pre-dawn hours. Since the 1920s, with the rise of artificial lighting, our modern condition has become increasingly tied to efficiency and, inevitably, to nervous fatigue. The International Style, X-ray architecture, the Bauhaus Modernism etc., all inevitably contributed to promoting electrified daylight as a tool for productivity, extending daytime into the night and celebrating it through luminous glass structures that punctuated the nocturnal landscape. As early as 1932, Marianne Brandt—renowned designer of the Bauhaus School—was already questioning how far the human body could be pushed: could we truly adapt to the very transformations we had brought about through technology? As the philosopher Vilém Flusser suggests [Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images], it is crucial to restore a balance between light and darkness and to adopt a more holistic approach to design—one that is attuned to natural biological rhythms and the cycles shaped by daylight.

Architectural spaces must re-establish this essential dialogue between the human body and the environmental rhythms of light—supporting temporal awareness, physiological regulation, and perceptual connection. Early examples of schools that embraced natural lighting and open-air philosophies offer valuable precedents. The Asilo Sant’Elia in Como, designed by the Italian rationalist architect Giuseppe Terragni (1937), was among the first to articulate a pedagogical vision through architecture: large windows, generous verandas, and open-air spaces facilitated a seamless integration of body, light, and space. In the US, Richard Neutra’s school designs (1935) similarly sought to harmonise nature, light and health decades before the term ‘biophilia’ was coined.

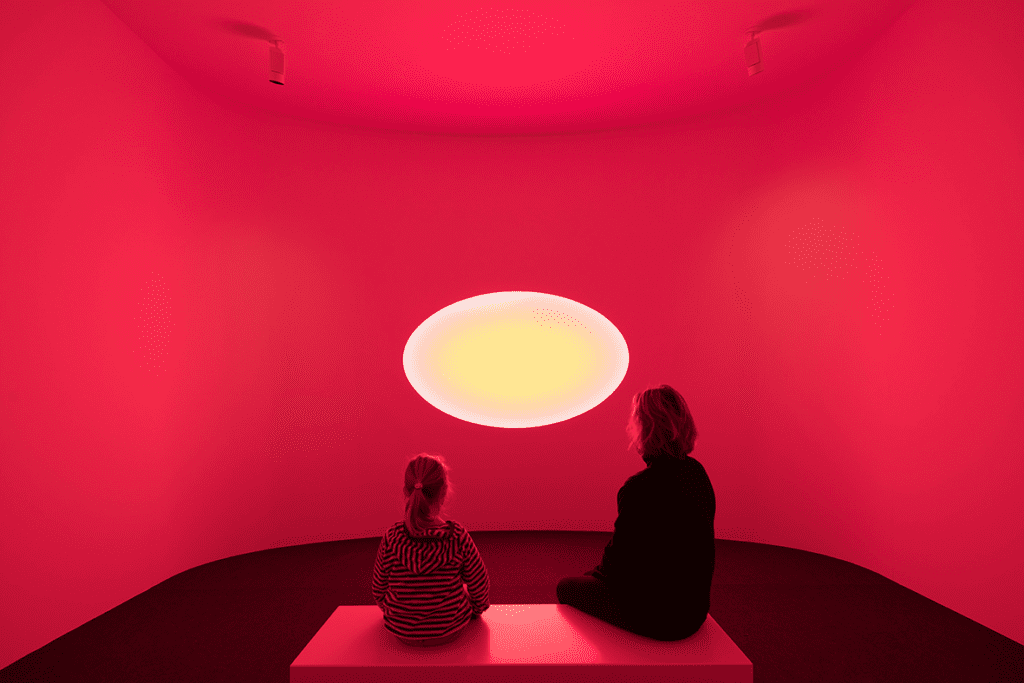

When designing to support sensory balance, the emotional aspect of light is often overlooked. Light modulates our limbic system—the brain’s emotional centre—by activating pathways related to memory and mood, therefore contributing in shaping atmospheres that guide behaviour. Its temperature, diffusion, and intensity affect how safe, open, or energised we feel within a space [Schledermann et al., 2019]. Zumtobel’s concept of “Limbic Lighting”, for example, builds on this understanding, tailoring lighting scenarios to foster positive emotional states, since emotional tone shapes learning capacity. Contemporary design is beginning to reflect these insights, shifting the role of light from a purely functional element to an emotional and experiential one, meant not only to illuminate but also to cultivate perception, presence, and wonder. A compelling model of light’s impact on emotional perception and health is found at the Kinderspital Zurich, where James Turrell has created a permanent light installation. More than an artwork, this is an immersive field of chromatic light that uses coloured light to regulate mood, circadian rhythms, and emotional recovery in young patients — a model that could inspire sensory-centred learning environments. Projects such as Els Colors Nursery in Manlleu by RCR Arquitectes experiment with this beautifully, using tonalities of coloured glass and natural light to create immersive atmospheres that modulate perception throughout the day: colour becomes an ambient language that supports calm, orientation and affective presence.

A similar approach has been experimented with in Témenos — from the Greek “portion of sky,” “sacred enclosure” — a space that empties itself of everything to dissolve into the boundless and infinite. It is an immersive light and sound environment designed to support emotional regulation and physiological restoration and is flexible in both function and context. Built as a prototype in 2019 in northern Italy, the space uses calibrated lighting and acoustic fields to blur architectural boundaries, modulate sensory input and induce states of perceptual enhancement. Empirical testing revealed heightened self-awareness and significant emotional attunement, indicating its relevance not only as an art space, but also for schools and clinical settings. As a multi-use environment, Témenos offers a pause in the city — a model for sensory regeneration in spaces of leisure, care and education, adaptable to the needs of learners, educators and the broader public.

How amazing would it be if every school could offer such a space?

Natural light access, dynamic light cycles, and temporal sensitivity should guide design and reconnect learners to nature, time, their internal rhythms and their true physiological and psychological needs. The same is true for sound. While light regulates time, rhythm, and visibility, sound grounds us in presence, relation, and affect. It is in fact through listening that we first connect to others and to the environment. In learning environments, sound can become a social and spatial force, shaping how we feel, focus, and participate.

Research in school acoustics has long emphasised the importance of auditory clarity and noise reduction for cognitive performance. Excessive background noise — whether from reverberant surfaces, HVAC systems, or external traffic — negatively affects speech intelligibility, working memory and attention. Studies show that a reduction in reverberation time and background noise can significantly improve reading speed, comprehension, and overall academic achievement [Brill et al., 2021]. Acoustic comfort is thus not merely a technical issue — it is a matter of accessibility, inclusion, and equality.

But the paradigm of mere insulation is not enough. Design should not merely aim to reduce sound but to open to it and curate it, moving from silence to resonance. Just as we speak of biophilic design, it is crucial to propose a new “ecology of vibration”, an acoustic biophilia where the architecture becomes receptive to the voice, to soft footsteps, to birdsong or rustling leaves, and encourages sonic participation with the world. Emerging studies show that certain natural or ambient sounds in schools—such as birdsong, flowing water or familiar human murmurs—are often perceived as comforting and enjoyable, rather than disruptive, and can therefore enhance the perceived restorative quality of learning environments [Zheng et al., 2025; Visentin et al., 2023; Klatte et al., 2010], as well as significantly improve short-term memory and sustained attention [Shu et al., 2019]. Most significantly, a systematic review by Pellegatti and colleagues analysed the cognitive effects of classroom acoustics — especially ventilation-related sounds — and confirmed that certain types of natural ambient sounds directly enhance attention span, short-term memory, and perceived comfort during learning tasks [Pellegatti et al., 2023]. This allows us to move from noise reduction to sensorial enrichment: instead of isolating children from sound, we can teach them to listen, to attune to themselves, to each other, to the shifting tonalities of their surroundings. In this way, listening becomes learning and soundscapes become pedagogical atmospheres.

A controlled acoustic permeability of space is key, as it fosters connection with both the environment and the social life of the school. Material choices, spatial proportions, and architectural form — including its openings — all influence how sound is perceived: whether it lingers, echoes, flows or fades. Projects such as Fuji Kindergarten in Tokyo by Tezuka Architects and The Green School in Bali by IBUKU/PT Bambu embody these acoustic and ecological intentions in inspiring ways. Fuji’s elliptical design dissolves barriers between interior and exterior, allowing children to roam freely and absorb light and sound from the open air and surrounding trees. At The Green School, light filters through bamboo structures and learning unfolds in direct dialogue with the natural landscape. Both examples challenge the rigid boundaries of conventional classrooms, offering instead porous, multisensory spaces that support freedom, rhythm, and ecological attunement. As Gaston Bachelard writes in The Poetics of Space, space is like a nest: not simply a place of retreat but a primordial spatial archetype shaped from within, from the body itself and its needs. In this sense, learning spaces can be designed to absorb noise, soften reverberation and enhance sonic subtleties: an architecture that absorbs harshness, celebrates nuance, and restores sonic proximity – and therefore emotional proximity – to the world.

Sound, like light, can guide us gently into presence, creating spaces that are not only functional, but also affective, inclusive, and alive. The challenge for contemporary architecture and design is surely to move beyond simply correcting for physiological deficits or optimising productivity goals, but to support human beings in their full perceptual, emotional, and cognitive complexity. Light and sound play a fundamental role in the interplay of elements and relations that architecture cultivates, strongly contributing to a spatial narrative that affects how people navigate, dwell, and emotionally connect to a space.